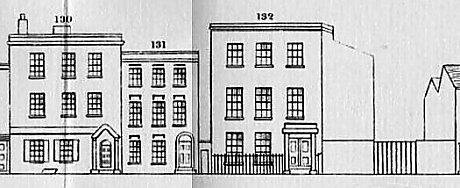

No. 130-132 High Street

In 1842, according to the Charpentier guide to Portsmouth (see right), this section of High Street comprised three houses and a piece of waste ground. Of the three properties, No 130 has been completely rebuilt since that time, No. 131 has survived largely intact and No. 132, as shown, is intact but later incorporated the waste ground as 132½ (132a, b and c in 2011), also known as Cambridge House. All of the properties would have been primarily residential accommodation throughout their existences but also at times offices for professional services such as solicitors and dentists.

There is only one known photograph of these buildings from the 19C and it must have been taken sometime around 1880. The full image is of the Cambridge Barracks on the other side of the road, but it also captures Nos 130 and 131 at a very oblique angle (see left). No. 132 is set back from No. 131 and is obscured by it but Cambridge House can be seen. It is a most useful image.

From the photograph we can determine that the building closest to the camera bears a strong resemblance to the No. 130 shown in the Charpentier drawing, the cornice above the ground floor windows and the pedimented lintel to the door are particularly comparable. It is noticeable that whilst the cornice overlaps the ground floor brickwork by an inch or two, the first floor brick work appears to overlap the cornice by a similar amount. However, if that were the case one would expect the cornice to continue on the right hand side of the lintel which, in the drawing, it doesn't. The only significant departure from the drawing is that the brick lintels above the ground floor windows are arched in the photograph whereas they are horizontal in the drawing. The shiny nature of the brick strongly suggests that the facade is built using black vitrified bricks, and although we can't see them, the edges and window surrounds are almost certainly dark red brick. The evidence we see in the photograph suggests that this is the building that stood here in 1860.

No. 131 is certainly an old building as a trip around the interior, courtesy of the current occupiers Dan and Gail of 131 Design, proved. There are two significant differences between the structure as it is in 21C and that portrayed by Charpentier. The first is that the windows on the right, above the door, no longer exist and the second is the door lintel which whilst curved in both images, can be seen in Charpentier to be semi-circular whilst in the 1880s photograph it is a flatter arc, as indeed it remains today.

There seems to be insufficient space to the right of the existing windows for two more to have been present whilst retaining the symmetry we see in Charpentier. This suggests that the whole, or part, of the facade may have been rebuilt at some stage, with the surviving windows having been moved to the right. This notion is supported by the fact that even in the 1880s the facade is rendered and this was a common way of concealing the existence of unmatched brickwork. Confirmation for the proposal that the render is a late addition comes from the pillars either side of the door which are partially buried in the render whereas one might assume they originally stood proud of the brick face.

Looking at it today, No. 132 appears to have retained the same basic structure since the 1842 drawing but because it is set back the photograph cannot confirm that it has always been so. The 1861 OS map shows that by that date Cambridge House had been built over the waste ground, however there is something odd about the evidence from the map which gives actual widths of all three original structures at that date to be 26'6", 18'0" and 37'0" with Cambridge House as 33'0". Measurement on the ground today confirms that the first two have retained their same respective widths but No. 132 is now only 30 feet wide and Cambridge House is 40'0" wide. There is a doorway to No. 132a on the left of Cambridge House and the map shows the limit to No. 132 to be the right hand side of that doorway. Further investigation will be needed to resolve this matter.

It is noted that in 1842 the main door was flanked by two columns supporting a simple portico, neither of which have survived, though the roof has been replaced in a rudimentary manner.

There is another unusual factor in the construction of No 132. Most of the three storey houses on High Street have shorter windows on the top floor, partly for proportional reasons but also because that would have been the area occupied by the servants, but the architects of No. 132 went one stage further and made those windows narrower. The windows to the first two storeys are 4'9" wide whilst the top set are 4'3" in width. No. 132 seems to be the only building on High Street where this happens.

The height of No 131 can be determined with some accuracy using the average height of brick courses of the 21C house at No. 130 (10 courses are equivalent to 2'6"). This gives a height of 30'6". Using this figure to compare the heights in Charpentier we get a height for No. 130 of 34'10". The height of No. 132 (using the brick dimensions) is 40'0", which would make a lot of sense as this would give the facade dimensions of 30' x 40', a very classical arrangement.

Cambridge House is the most elaborate building on High Street and has arguably been so since it was constructed around 1860. The level of ornamentation is quite unprecedented in either private residence or public building. Perhaps it is indictative of the confidence felt by the community in the middle of the Victorian period, just after the Great Exhibition of 1851, a time when there were very few new buildings constructed on High Street.

At first glance, the building suggests that it is utterly unaltered since the date of it's construction and yet this cannot be so. There is evidence of deterioration in the stonework and much of the detail has been covered by the extensive application of masonry paint which in some cases almost entirely conceals the original design. In particular, the render above the ground floor still has the feint marks where faux stonework had been indicated. Also, the window sills to the second floor originally boasted an intricate herringbone motif which is baraly discernable in the 21C.

Looking at the building today it seems natural to assume it had always been white (or cream) coloured but the photograph from the 1880s shows it to have formerly been a much duller shade, possibly even grey, which would be understandable if the builders were trying to create an impression that the whole were made of stone rather than render.

Documentary Evidence

Hunt's Directory (1852) - Charles B Hellard, solicitor and insurance agent, 132 High Street;

Post Office Directory (1859) - John Maddock, RN, 131 High Street; Charles Bettesworth Hellard, solicitor and insurance agent, 132 High Street;

Kelly's Directory (1859) - Chas B Hellard, clerk to Co. Magsts and to Portsmouth Burial Board and Improvement Commissioners and Insurance Agent for Eagle Life and Palladium Life, 132 High Street; John Martin, Dental Surgeon, 132 High Street;

Simpson's Directory (1863) - Messrs E and D Bell, 131 High Street;

Harrod's (1865) Directory - Charles Bettesworth Hellard, surgeon, and Alexander Hellard, 132 High Street; John Martin, Dental Surgeon, 132 High Street;

The 1861 Census records:-

Schedule 119 - Edmund Clark (40, Cork Merchant, employs 100 men and 5 clerks), his wife Hester (33), an unnamed 6 year old son, with servants Elizabeth Guilding (35), Ann Fry (29), Jane Phippard (21) and George Williams (18).

Schedule 120 - John Maddock (72, RN Paymaster Retd.), his daughter Caroline Dunbar (42), son-in-law Charles Dunbar (41), grandson Charles Dunbar (11), granddaughter Constance Flood (9) and two servants

Schedule 121 - Charles B Hellard (53, Mayor of Portsmouth), his wife Elizabeth (59), daughter Elizabeth (27), son, Alexander (24, solicitor), son Joseph (22), daughter Charlotte (20), son Henry (14), son Edwin (12) and servants Louisa Burson (30) and Elizabeth ? (21)

Schedule 122 - John Martin (49, Dental Surgery), his wife Frances (48), his nieces Elizabeth Boycott (23) and Fanny King (11) and servants James Allan (23, Coachman), Joseph Hile (17, Footboy), Harriett Dollar (40, Cook), Mary Ann Morant (19) and Sarah Ryall (30)

The census records an uninhabited house after Schedule 122.

The first three schedules clearly relate to Nos. 130-132 High Street respectively. Schedule 122 refers to part of Cambridge House but it is not known whether the vacant premises is part of the same building or the neighbouring house. Either way, given the scale and decoration of Cambridge House, it would seems that dentistry was a very profitable profession.

Summary

The evidence we have points to No. 130 appearing in 1860 as it did in 1842 and that is how it will be modelled, apart from the arched lintels to the ground floor windows which were almost certainly in place throughout the history of the building. The exact design for the doorway cannot be known for certain as the only detailed information we have is at such an oblique angle that the interior is obscured. From the 1861 OS map we know that this was a very substantial property, extending all the way back to the Baptist Chapel in St Thomas's Street and having a grand bay overlooking a small garden at the rear.

There is no firm date for the alterations to No. 131 but we know that they had taken place by the 1880s. The model will portray the building as it appeared after the changes had taken place. There was an alleyway between Nos. 131 and 132 in 1842 and it survives today, though has been partially enclosed. It has a width of 2'9".

No. 132 will be modelled as it appears in the Charpentier drawing, with details drawn from the surviving building, whilst Cambridge House presents the modeller with a problem not previously encountered. On every single building so far constructed, the finished model has appeared too pristine, when we know for certain that they would have shown the ravages of perhaps more than a century of existence, the limiting factor being the modeller's skill. In the case of Cambridge House the opposite is true in that in 1860 it would have been a very recent construction with all the detailed decoration clearly visible. In the intervening 150 years however the building has suffered a degree of degradation not the least of which being the application of many layers of masonry paint which nowadays partially obscures the original design. It will require very careful examination of the existing surfaces in order to determine the full originality of the facade design.