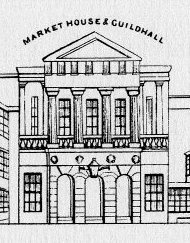

Nos. 42-43 High Street (The Market House and Guildhall)

The Market House and Guildhall was one of the most outstanding buildings on High Street. It had been opened only four years before the publication of the Charpentier panorama of 1842. It replaced an earlier incarnation which had stood in the centre of the High Street.

The plot on which the building was erected was formerly occupied by a public house (The White Horse), two tenements, a store, two houses in Pembroke Street and a portion of the Dolphin yard. The foundation stone was laid on May 24th 1837 (Princess Victoria's birthday) by the Mayor William Cooper. The building was designed by Mr. Benjamin Bramble and constructed at a cost of £4000. It was opened on June 28th 1838 (Queen Victoria's Coronation Day).

The building consisted of an open market on the ground floor with a Council Chamber and several municipal offices above. It was constructed on an "L" shaped plan such that a second grandiose facade gave access from Pembroke Street, that side of the building being used as a Police Station until 1855. Although there are no records to suggest how the Market operated the OS map of 1861 provides more evidence of internal structures than is usual. It shows a row of small, cubicle sized rooms running down both the north and south sides of the ground floor, the south side row extending well into the courtyard at the rear. These must have been permanent kiosks for some traders whilst the rest may have had to make do with temporary structures along the centre of the building, though it barely seems wide enough to accommodate them.

The OS Map gives us a width for the Guildhall of 34 feet, though unusually the map shows side walls of considerable width whereas for most other buildings a simple dividing line is indicated. It is not clear how this may affect the actual width. The height of the building can only be assessed in comparison to the Dolphin Hotel next door, the height of which is known with some accuracy.

Though considerably larger than its predecessor it quickly ran out of space for the Council officials and after only 42 years the decision to move on was made. This did not actually happen until 1879 when the New Guildhall in Guildhall Square was opened. Thereafter the Market House was converted into a museum, a role it fullfilled in gloomy silence until hit by German bombs in 1941. The ruined facade remained in place for more than 10 years before being finally demolished.

Further details of the process by which the Market House and Guildhall came into being can be found in our Town Halls of Portsmouth article in the "Places" section.

Summary

It is evident from the Charpentier drawing and later photographs that little change occurred to front of the building between it's construction and demolition. It is apparent however that windows were introduced to the two arches flanking the central doorway and though no date for this is known it seems reasonable to assume that the change occurred during the transition from Guildhall to Museum. An early drawing suggests that there were doors giving access through all three arches plus a further door on the left hand side which was also later converted into a window.

The detailed construction is going to be problematic on a number of levels. We shall start with a look at the ground floor which contains five apertures across the full width. The purpose of these changed over the years according to usage of the building but two early drawings contradict each other in that one shows a 10 foot high door in the left hand opening with a skylight above it, whilst the other shows a window. In both, the right hand opening has a sash window running the full height of the section. As all later photographs of the building show a door on the left it is presumed that the initial design contained a window but that this was changed at an early date.

The means of entrance via the three arched openings is difficult to ascertain as any doors that may have been present were set back too far too far to appear in any illustration but there must have been some means of shutting the building, even if only at night time. There may have been open access during the day as the ground floor was originally a permanent market house to which customers and traders would have needed continuous entry, at least for the period the market existed at that location. There is a reference in the Hampshire Telegraph (3rd March 1860) that "the Council would not obtain full possession of the Guildhall for at least a twelvemonth" which may mean that the market was being evicted at that time. It seems likely that the left hand window was replaced by a door at this time.

Examination of the stonework to the arches leaves us with the impression that the architect was an amateur. We know that the design for the building that was accepted by ballot of the Council was drawn up by Benjamin Bramble who in 1836 was elected to serve as a Councillor and was therefore in office at the time. This smacks somewhat of civic corruption, especially when one considers that in Robert East's "Extracts from the Portsmouth Records" Benjamin Bramble is described as a builder at the time of his election rather than an architect. It is interesting to note that in 1836 there were no architects serving on the Council, nor anyone else with a background in the construction industry.

The evidence for suggesting that the design was amateurish in at least one aspect is the way the three arches have been laid out. Each outer arch has a perfectly semicircular head whereas in the central arch it is squashed into an ellipse (with the major axis running horizontally). By scaling up photographs and correcting for perspective we can say that the two side arches are approximately 3' 8" in width whilst the centre is 4' 10" wide. Despite this difference all the arches are virtually the same height (there may be a difference of an inch or two) and all spring from columns of the same height. The stonemasons have plainly had a problem with this as they wrestled to fit the masonry chamfers into a harmonious pattern. In particular they found themselves obliged to assign three narrow keystones to the central arch rather than the single stone over the others. They did a creditable job given the circumstances but the end result is clumsy. Further evidence is available at balcony level where the principle fluted columns are not aligned over the arches in any meaningful way. Also the balustrading is inconsistent, using rectangular side supports for the outer sections but not for the inner.

The back wall of the balcony is indistinct in most photographs but it seems most likely that there are a set of five tall, narrow windows aligned to the centre lines between the columns and the columns and the outer walls. This is slightly surprising in that if all the apertures in that wall are windows how do the Councillors, or anyone else, get out onto the balcony, and if there is no door, why use up so much space for purely decorative effect when it is acknowledged that the building is too small.

The inelegance of the architecture is further illustrated around the pediment where some of the decoration is coarse and looks as though it was left over from another job (possibly the previous Town Hall) and crudely tacked onto this building. Some cornices and other decorative features that would normally form a continuous band are disjointed for no obvious reason.

The architecture of the building may be a little amateurish but this does not affect the way the model of the Guildhall is built, but it is a complex structure and we don't really have enough information to be absolutely sure of it's accuracy.